A Tale of Two Messerschmitts By: Richard Corey |

||||||||

| Introduction: | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| I. A Case of Recycled Aircraft. |

||||||||

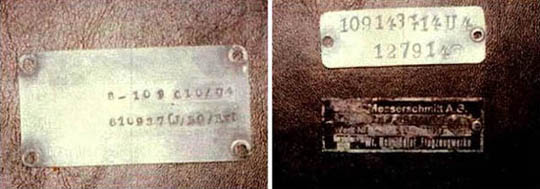

There are those who contend that all Me-109 G-10s were built new at the factory. Where this might be true for Me-109 K series that followed the G-10, or of Luftwaffe aircraft in general, it does not explain why both 610824 and 610937 have two manufacturer’s data plates attached to the fuselage. Many wartime photos seem to show this and sources indicate that this is a sure sign of older, existing aircraft being rebuilt to G-10 standards. By October 1944 when the G-10 first appeared, the Reich was being systematically pounded into rubble by the Allies “round the clock” bomber offensive. Everything was in short supply. Raw materials were dwindling, fuel supplies were running out, transportation of any kind had broken down and factories were forced to disperse into the countryside with all the usual bottlenecks in production associated with such a move. Yet in 1944, Germany produced more fighters than in any other year of the war. Given the conditions at the time I feel that this feat could only be accomplished by recovering repairable airframes and re-manufacturing them into new fighters with the latest equipment upgrades. Indeed, the goal of the Me-109 G-10 program was not a further development of the G series, but an attempt to convert older, repairable aircraft such as the G-6 and G-14 to a standard of performance roughly equal to the K-4 that was still under development. My best example of this practice is the Erla Machinenwerk GmbH of Leipzig who had been building the Me-109 under license since 1937. Ingenieur Fritz Bartsch, a long serving staff member was tasked to organize a Reparturbetrieb (a large scale repair depot) in Belgium. The site selected was the old Minerva automobile works at Mortsel, a suburb south of Antwerp, located near the Deurne-Antwerp Airfield and conveniently close to a railway siding. Civilian workers and contractors willing to work for the Germans were found, the necessary tools and machinery brought in and from 1941 until the Allies were literally knocking on the front door with the Germans quickly exiting out the rear, Frontrepartutbetrieb GL Erla VII was an ongoing concern. Trainloads of damaged Me-109s arrived at this depot and were quickly stripped down and overhauled. The latest modifications were incorporated during repairs along with the latest Umrust-Baustaze (factory conversion sets) and then the refurbished aircraft were repainted, test flown and delivered to front line units. All of this activity didn’t escape the notice of the Allies and Erla VII did become a victim of a rather abortive bombing attempt by U.S. forces on April 5, 1943. Little damage was done and Erla VII was used for series repair of the Me-109 until September 1944, when they were forced to retreat in the face of advancing Canadian forces. From there, they set up shop in Munster until the end of the war. Although most of this story happened before the Me-109 G-10 entered service, I feel safe in saying that the German aircraft industry continued this practice until the war’s end.

|

||||||||

| II. G-6, G-14 or G-10? | ||||||||

Along with the identities of 610824 and 610937, there seems to be a bit of confusion over what model of Me-109 G they actually are. I have seen 610824 listed as a G-6 and 610937 listed as a G-14. I’m not sure if this is a case of mistaken identity or publications stating what the aircraft were originally before being re-manufactured into G-10s. 610824 was rebuilt from a G-6 fuselage. Although the original manufacturer’s data plates were removed prior to its being restored, a fuselage sub-assembly plate was found inside the aircraft showing that it was a G-6 fuselage. This information was passed along in the restoration process, but unfortunately the information on the plate was never recorded. The original data plates for 610937 were intact however and show that this machine was rebuilt from a G-14, werke number 127914. Photographic evidence shows all the trademarks of the G-10 series. The refined cowl bulge, larger supercharger intake, the larger Fo-987 oil cooler, larger tires and corresponding wing bulges. The DB-605D engine and characteristic chin bulges certainly disqualify the G-6. Not even a G-6/AS would exhibit all of these features. The G-14 is a different matter and is easily confused with the G-10. The only real way to tell them apart is by the werke numbers. These numbers were a code used by the German aircraft industry to identify the model and manufacturer of a particular airframe. These blocks of construction numbers were distributed to manufacturers under strict guidelines by the RLM (German Air Ministry) and once a number was assigned, it was never changed. The prefix 610… was reserved for G-10 aircraft built by Wiener Neustadter Flugzeugwerke. (WNF)

|

||||||||

| III. Histories. |

||||||||

After test flying, it was found not to be airworthy and made its journey to Cherbourg by truck, it was then loaded on the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Reaper along with many other captured Luftwaffe aircraft and left port on July 19, 1945. 12 days later it arrived at pier 14 in New York Harbor, it was trucked to Newark, New Jersey and finally arrived at Freeman Field near Seymour, Indiana on May 17, 1946. The aircraft was given a rather spurious paint scheme and the code: FE-124, this was changed later to: T2-124 when the Air Technical Service Command underwent re-organization and the Technical Data Laboratory Branch became part of T-2 Intelligence. 610824 was not used for research, but instead became a display aircraft in the early post war era touring various airbases. One of the last being Dobbins Army Air Base near Marietta, Georgia and was on display there with T2-118, a Focke Wulf Fw-190 D-13/ R 11.* With the end of World War Two, non-critical facilities like Freeman Field, which was being used to store surplus Axis equipment were being closed down and aircraft that weren’t earmarked for museums were to be scrapped. This probably would have been the fate of T2-124 and T2-118 had it not been for the interest of Professor Donnell W. Dutton at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. In 1947, T2-124 and T2-118 were donated to Georgia Tech. The two airframes were not used officially by Georgia Tech. For research or evaluation, but were placed in storage for later display by the school’s nine member flying club. Sometime around 1955, Bud Weaver, an FAA inspector in Atlanta traded a working aero engine for the two aircraft. They were then stored out in the open at various rental properties owned by Mr. Weaver and soon became derelict due to vandals and exposure to the elements. It was at this time that 610824 lost its original wings. Someone had the local Trash Company haul it off to the dump! Mr. Weaver arrived in time to retrieve the fuselage, but it was too late to save the wings. If anything good could have happened from all this, then at least the weather had worn off the spurious paint job to reveal the original markings on what was left of the airframe. In the mid-1960s T2-124 and T2-118 parted company as John W. Caler of Sun Valley, California Valley purchased the remains of the Me-109. His intentions were to restore the aircraft (in his own garage!) and he was able to obtain a set of wings from a Czech Avia. He reportedly tried to re-skin the fuselage and because of a lack of proper tools and expertise, the results were not a professional looking job. This is supposed to be a clue to 610824’s identity. This project was eventually abandoned and the airframe sold to an unknown private collector, date unknown at this time. Somewhere between 1979 and 1984 it was sold to Doug Arnold’s Warbirds of Great Britain Collection and placed in storage at his Biggin Hill facility to eventually become a stable mate with our other Me-109 G-10, wk. nr. 610937. Some restoration work may have been carried out but cannot be confirmed. In 1989 it was sold to Evergreen Ventures and restored to static display condition by Vintage Aircraft Restorations LTD. of Ft. Collins, Colorado. Depending on which source you want to go by, restoration work was completed in 1995-1997. Since April 1, 1999, 610824 has been on display at The United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio as “Blue 4” of JG 300. An interesting side note here: As Freeman Field was a subsidiary of what was then known as Wright Field, it would seem that 610824 has traveled full circle since its arrival in the U.S. in 1946.

Somewhere between May and August 1945, 610937 and many

other aircraft were taken as trophies by units from the 6th Polk, (regiment) of

the Bulgarian Air Force and ferried to Bulgaria. The trip must have been a harrowing one

to say the least. The airfield was situated between the British and Soviet zones of

occupation and the aircraft had to fly through the British zone. The English reacted by

sending a protest to the Soviet Command to “stop flying German planes in their zone.”

Two Spitfires were dispatched to patrol the area and anti-aircraft units occasionally

opened fire on these “trophies” with at least three of them reported to have been shot

down. The next stop

was Pech Airfield in Hungary, where the Hungarians rushed the field thinking that they

were welcoming their pilots returning home. They had a rather unpleasant surprise seeing

that the aircraft were piloted by the Bulgarians. After a stop in

Belgrade, they finally reached Sophia. Not much is known about the service history of

these Bulgarian Me-109s. Many were transferred from the Karlovo Airfield to the Burshen

Airfield near Silven and were actively flown by the 2nd and 3rd

Orlyak (group) of the 6th Polk until they converted to the Soviet built Yak-9.

Some of these Me-109s served in the training role as late as 1950, with the last of them

being cut into scrap metal in 1951. In 1947, the

Paris Peace Treaty limited the size of Bulgaria’s Air Force and some of its excess

aircraft were sent to Yugoslavia in military equipment trade negotiations between the two

countries. 610937 became part of a shipment of 59 Me-109s of assorted variants to be

traded for a number of fuselages and tail units of Il-2 Strumoviks. After being

transported to Zagreb by rail, the aircraft were refurbished, repainted and 610937 became

“White 44”, Yugoslav Air Force s/n 9644. White 44 was flown by either the 83rd

or 172nd fighter wing based at Cerklje Airfield and may have been flown on

patrol sorties along the Italian frontier during the confrontation between Yugoslavia and

Italy over the free zone of Trieste. White 44’s last recorded flight was October 17,

1950. Total flight time in service: 35 hrs. 15 mins. The aircraft was

placed in storage until 1953, when it was declared scrapped and donated to a technical

school known as the Machine Facility in Belgrade. It was used as an instructional airframe

until somewhere between 1977 and 1979 when it was transferred to the Yugoslav Aviation

Museum in Belgrade. Apparently the museum didn’t have the funds to restore the airframe

and in 1984, it was sold to Doug Arnold’s Warbirds of Great Britain Collection. Some

restoration work may have been carried out, but as with 610824, is un-confirmed. In 1989, it was

sold along with 610824, to Evergreen Ventures and in 1991 it was sent to Vintage Aircraft

Restorations LTD. at Ft. Collins, Colorado where after 5 years it was restored to

flight-worthy condition. It was painted to represent an aircraft flown by Germany’s

leading ace, Eric Hartman and is on display in preserved condition (fluids drained) at the

Captain Michael King Smith Evergreen Aviation Educational Institute in McMinnville,

Oregon. |

||||||||

| IV. Photos. |

||||||||

A

photo of T2-124 taken in the 1960s when Bud Weaver owned the aircraft. Note the large oil

cooler, supercharger intake and chin bulges. All trademarks of the G-10

An

engine shot of 610937 showing the DB 605D engine and redesigned engine bearer.

A painting of what 610937 may have looked like when it was in service with the Yugoslav AF as “White 44”, s/n 9644.

|

||||||||

| Credits: |

||||||||

Djordje Miltenovic for finding the information confirming wk.nr. 610937 and the excellent web site he and his brother Alexander run at: https://members.tripod.com/YUModelClub/

|

||||||||

| Sources: |

||||||||

Brian Nicklas of NASM and Doug Lantry of USAFM.

|

||||||||

| Books: | ||||||||

Eagle Files #2, Yellow 10 by Jerry Crandall |

||||||||